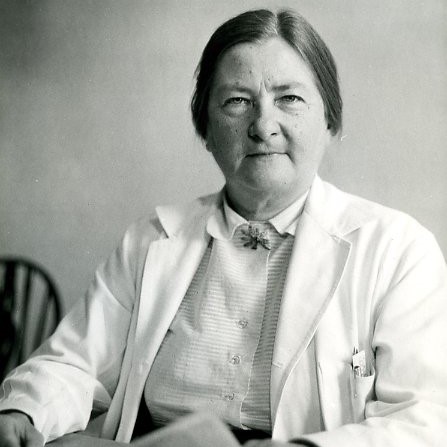

Dorothy Hansine Andersen

Authors: Dr Deirdre Gilpin, Professor Michael Tunney and Professor Stuart Elborn

In biographies of Dorothy Hansine Andersen, she is frequently described as “unladylike” and “wind-blown”. She was a heavy smoker and listed canoeing, carpentry and roofing among her hobbies. She kept a particularly untidy lab, where she held semi-annual “Glüg” parties- a nod to her Scandinavian ancestry. She studied medicine in an era when being a woman barred access to many specialities. Yet despite this, she identified two diseases: Cystic Fibrosis (CF) and Andersen’s disease (a disorder of glycogen metabolism), developed a diagnostic technique for CF, the basis of which is still used today, and her understanding of cardiac malformations was key to training surgeons preparing for open heart surgery.

Her pathway to these important discoveries was neither easy nor conventional. She was born in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1901. Her Danish father was a farmer, who died when she was 13 years old. She cared for her invalid mother until her death, six years later. After supporting herself through college, she began studying medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, one of only five women in her class. After graduating in 1926, she moved to study anatomy at the University of Rochester in Rochester, New York and the following year applied for a surgical residency at Strong Hospital in Rochester. Strong had never admitted female residents before, and despite her excellent qualifications, Dr Andersen was denied admittance because she was a woman.

Whatever the personal grievance at this obstacle, she instead changed direction and accepted a research position at Columbia University in New York, before moving on to the Babies Hospital at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Centre. As part of this work, Andersen carried out a number of autopsies on children who had coeliac disease. At autopsy, many had scars and fluid filled cysts on their pancreas, and similar damage was observed on their lungs. Andersen’s curiosity was piqued, and she put her training as a clinical pathologist to work, exploring medical records, and carrying out many autopsies, some on children with coeliac disease. Her genius was spotting a pattern among an apparently diverse range of symptoms: failure to thrive, pancreatic insufficiency, respiratory infections, mucoid congestion, and linking those with the pancreatic histology she observed. In 1938, she published a paper describing these findings in 49 patients, in which she named this condition “Cystic Fibrosis of the pancreas”.

Not content with a description of this condition, Andersen and colleagues then worked to understand the pathology underlying this disease and to identify ways in which they could improve the lives of children with CF. Recognising the disruption to the pancreas, in 1942, she developed an assay to measure pancreatic enzymes in duodenal juice. This meant that these children could be identified, albeit, via a complicated enzymatic assay. However, she also recognised that in hot weather, CF patients did not fare well: during a heat wave in 1948, and in subsequent years, her colleague Paul di Sant’ Agnese, developed a method to detect sodium and chloride changes in sweat, which is now the basis of modern-day CF diagnosis. During the 1940s, she published further research looking at the impact and improvements to life expectancy which could be gained by treatment of respiratory infections with antibiotics.

By her own admission, she is alleged to have said that she was “the only person in the world who knew about CF” – desperate parents from all over the USA travelled to her New York clinic with their children. Eventually, over 600 children were referred to her clinic, where she and Dr Paul di Sant’Agnese laid the foundation of modern CF care: early diagnosis of CF, aggressive treatment and specialised care, all of which have increased the life expectancy among CF patients. This tremendous achievement owes its foundation to Andersen’s painstaking and meticulous scientific investigation and paved the way for the identification of the gene responsible for CF, and present-day drugs, which can modify and potentiate the defective CF protein, thus continuing the transition from an early-fatal to a life-limiting chronic illness.

These critical insights were as the result of the tireless insight and efforts of a rugged individualist. Sadly, Dr Andersen’s heavy smoking habit caught up with her in 1963, and she died after developing lung cancer. She received much recognition for her work: the Borden Award for research in 1948, the Elizabeth Blackwell Award in 1952 and the Distinguished Service Medal of the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Centre, in 1968. She was an honorary fellow of the American Academy of Paediatrics and an honorary chair of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. In 2002, she was inducted in the National Women’s Hall of Fame. However, nothing speaks to her contribution to the field so eloquently as her last paper, in which she described CF in a new category of patients: young adults. When she began her research in the 1930’s, all of her patients died in childhood.

Acknowledgement

With many thanks to Prof James Littlewood OBE, whose valuable and critical insight in this area was much appreciated.

Professor Elborn is a well-established international leader in healthcare having driven major changes in healthcare delivery in the field of cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis. He has spent decades researching Cystic Fibrosis (CF) and his work has led to major breakthroughs in treating the condition.

Dr Deirdre Gilpin

Dr Gilpin’s research is focussed on investigating infection in chronic lung disease and determining the contribution of the many microbes present in the lung, to development of disease and exacerbation in cystic fibrosis, COPD and bronchiectasis. She is also involved in determining the effect of cigarette smoke and electronic cigarette vapour on the key lung pathogens, investigating the significance of MRSA infection in the lungs of people with CF and developing novel outcome measures for assessing antimicrobial efficacy in the CF lung. She is currently a Swan Champion in the School of Pharmacy, and chairs the Queen’s University Swan Champions Network.

Professor Michael Tunney

Professor Tunney's research focuses primarily on the improved detection and treatment of lung infection in patients with respiratory diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF), bronchiectasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Professor Tunney's laboratory is a world class centre of excellence which aims to develop the next generation of diagnostic tools and treatments, in order to alleviate and prevent chronic respiratory infection.