Irish Republicanism and Nazi Germany

How did Irish republicans view Nazi Germany during the 1930s and the Second World War? Were republicans who advocated an alliance with Germany motivated solely by tactical considerations – my enemy’s enemy – or did ideological considerations also play a part? Historian Brian Hanley considers the evidence.

How did Sean Russell, the IRA’s Chief of Staff come to spend the summer of 1940 in a villa in Berlin’s leafy Grunewald? In the German capital, basking in the aftermath of the rapid conquests of France, Norway and the Low Countries, Russell was given diplomatic status with access to rationed goods and food, as well as use of a car. His villa was equipped with a radio gramophone and map facilities and a young Austrian aristocrat was assigned to him as a driver and interpreter. The IRA leader visited military facilities and met Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim Von Ribbentrop. He urged that the German High Command make use of the IRA to strike at British forces in Northern Ireland as part of their Operation Sealion (the plan for the invasion of Britain).

In August Russell made preparations for a return to Ireland to oversee the implementation of these plans. Along with Frank Ryan, who had been an IRA comrade of his until 1934, Russell travelled home onboard a U-Boat submarine. However he became violently ill, suffered from a burst ulcer and died at sea and was buried with full German naval honours. Russell’s attempts to link up with Nazi Germany were well known by the time a statue to him was unveiled in Dublin’s Fairview Park during October 1951. Indeed a republican newspaper covering the event described his Berlin sojurn in some detail. Yet many still dispute that Russell collaborated with the Nazis, painting him as a simple military man unconcerned with political matters. Others suggest that he and the IRA had no knowledge of Nazi policy and were simply taking advantage of ‘England’s difficulty being Ireland’s opportunity.’

Sean Russell and the German alliance

There is little evidence that Russell was an ideological supporter of Nazism. Indeed his long IRA career had been notable for his avoidance of political debates. Born in Dublin in 1893, Russell joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913 and fought in the Easter Rising, after which he was interned. He rose through the ranks of the IRA during the War of Independence, becoming Director of Munitions and a member of General Headquarters Staff by 1921. Opposing the Anglo-Irish Treaty after the Civil War, Russell remained an active IRA man, eventually becoming the organisation’s Quarter Master General in 1927. The IRA embraced left-wing policies during that period, but Russell remained aloof from political debates, though he was part of a delegation to the Soviet Union in 1925. Russell was popular with his fellow officers and rank and file IRA members, but seen as a practical military man rather than a politican. In the early 1930s the organisation had perhaps 14,000 members, and enjoyed some popular support. By 1936 however the IRA was in decline, riven by political divisions and facing a harsh clampdown from the government of Eamon de Valera. It was then that frustrated volunteers began to turn to Russell, hoping he could offer them military action and a way to win back support. By 1938, after a series of internal power-struggles, Russell had succeeded in becoming Chief of Staff with a promise to lead a new campaign against Britain.

There is little evidence that Russell was an ideological supporter of Nazism. Indeed his long IRA career had been notable for his avoidance of political debates. Born in Dublin in 1893, Russell joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913 and fought in the Easter Rising, after which he was interned. He rose through the ranks of the IRA during the War of Independence, becoming Director of Munitions and a member of General Headquarters Staff by 1921. Opposing the Anglo-Irish Treaty after the Civil War, Russell remained an active IRA man, eventually becoming the organisation’s Quarter Master General in 1927. The IRA embraced left-wing policies during that period, but Russell remained aloof from political debates, though he was part of a delegation to the Soviet Union in 1925. Russell was popular with his fellow officers and rank and file IRA members, but seen as a practical military man rather than a politican. In the early 1930s the organisation had perhaps 14,000 members, and enjoyed some popular support. By 1936 however the IRA was in decline, riven by political divisions and facing a harsh clampdown from the government of Eamon de Valera. It was then that frustrated volunteers began to turn to Russell, hoping he could offer them military action and a way to win back support. By 1938, after a series of internal power-struggles, Russell had succeeded in becoming Chief of Staff with a promise to lead a new campaign against Britain.

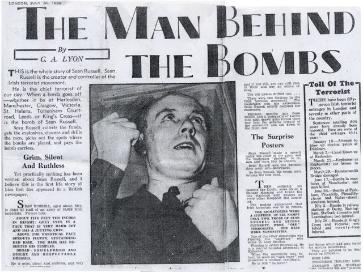

That campaign, which was to begin with bombings of targets in Britain was the brainchild of Joseph McGarrity, the IRA’s key supporter in Irish America. It was through McGarrity that Russell first made contact with German intelligence. In October 1936 Russell wrote to the Nazi ambassador in Washington, offering IRA support in any future conflict between Germany and Britain. Indeed the promise of German financial and military aid was key to Russell winning control of the IRA. One of his rivals for the IRA leadership, Tom Barry, claimed that the German-American Bund, the main Nazi organization in America, funded Russell’s campaign. In January 1939 the IRA’s bombs began to explode in English cities: though seven civilians and two IRA members would die as a result of the campaign it had effectively ended by 1940. In late 1939 Russell travelled to the US to raise more support and from there during 1940 he was spirited, via Genoa, to Germany.

That campaign, which was to begin with bombings of targets in Britain was the brainchild of Joseph McGarrity, the IRA’s key supporter in Irish America. It was through McGarrity that Russell first made contact with German intelligence. In October 1936 Russell wrote to the Nazi ambassador in Washington, offering IRA support in any future conflict between Germany and Britain. Indeed the promise of German financial and military aid was key to Russell winning control of the IRA. One of his rivals for the IRA leadership, Tom Barry, claimed that the German-American Bund, the main Nazi organization in America, funded Russell’s campaign. In January 1939 the IRA’s bombs began to explode in English cities: though seven civilians and two IRA members would die as a result of the campaign it had effectively ended by 1940. In late 1939 Russell travelled to the US to raise more support and from there during 1940 he was spirited, via Genoa, to Germany.

Irish republicans and support for Nazism

If Russell himself never expressed public support for Nazi policies, there were those in his organisation who were more enthusiastic. In July 1940 when a German victory looked likely, the IRA issued a statement in Ireland hailing the Nazis as ‘friends and liberators of the Irish people.’ In August the IRA confidently predicted that with the assistance of their ‘victorious European allies’ Ireland would ‘achieve absolute independence within the next few months.’ The IRA linked up with German agents who landed in Ireland and expected that it would play a role in any military operations against British forces in Northern Ireland. Left-wing critics of the IRA pointed out that the organisation was now lauding as ‘liberators’ a power that held ‘Abyssinia, Austria, Albania and Czechoslovakia’, anong others, in subjection. This, they noted, was particuarly ironic because during the early 1930s the IRA had strongly condemned Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy and offered solidarity to the victims of these regimes. Then, the IRA’s press had denounced the ‘bloody coericion’ imposed on Jews and left-wingers in Germany and condemned ‘Hitlerism’ as a ‘disease’. This illustrates that Irish republicans, including Russell, could not reasonably claim to have had no knowledge of the nature of Hitler’s regime. Until the mid-1930s at least, the IRA had been critics of Nazism and the various measures imposed by the Nazis had been widely reported in Ireland. By 1940, however, IRA policy had changed.

Part of the reason for this was practical: the Nazis were fighting the British. Another factor was desperation: by 1940 de Valera’s government was clamping down further on the IRA, interning and even executing its members. With little chance of overthrowing de Valera and even less of driving the British out of Northern Ireland, the Nazis offered the IRA its only hope of success. But there were also elements within the IRA attracted by Nazi ideology and by 1940 some IRA publications were parroting anti-Semitic propaganda. One, War News, even claimed that de Valera’s government was dominated by ‘Jews and Freemasons’ who were becoming the ‘new owners of Ireland.’ IRA members now cooperated with former members of the fascist Blueshirts in a variety of small pro-German organizations in Dublin and elsewhere. During 1940 the IRA even approached the former Blueshirt leader Eoin O’Duffy (once a sworn enemy of their organisation) and offered him a leadership position. But German espionage in Ireland came to naught and by 1941 the likelihood of German forces landing in Ireland receded. News of Russell’s fate took a long-time to reach the IRA and amid leadership turmoil the organisation turned further in on itself and was effectively crushed by 1944. In the internment camps and prisons both pro-Nazi and anti-Fascist factions emerged, while many activists dropped out, disillusioned.

Fortunately, how the IRA would have behaved had German forces actually landed in Ireland remains a hypotethical, if contentious, question. Across Europe nationalist organisations cooperated with the Nazis for a variety of reasons. Whether such cooperation was inspired by apolitical pragmatism or by sympathy for Nazism in the end would have mattered little: the results were always tragic. There is little evidence that our experience would have been any different.

Brian Hanley lectures in history at the Institute of Irish Studies, University of Liverpool. He is the author of The IRA 1926-1936 (2002), The Lost Revolution: the Story of the Official IRA and the Workers’ Party (2009) and The IRA: A Documentary History 1916-2005 (2010).