Rosamond Jacob and Frank Ryan

Who was Rosamond Jacob? What does her richly-documented life as an activist on the radical fringes tell us about politics and society in the Irish Free State? Why has her relationship with Frank Ryan proved a source of fascination for historians? Leeann Lane, Jacob's biographer, reports.

A life in activism

Rosamond Jacob was not a prominent figure in Irish history; she was a fringe activist, a foot soldier. Jacob was born in 1888 to lapsed Quaker parents in Waterford. The family were fully engaged in, and with, the political and humanitarian campaigns and ideas of the late nineteenth, early twentieth-century and Jacob’s childhood and adolescence was filled with debate and discussion on the Irish national question, the issue of female suffrage and the rights of both humans and animals. Jacob was a follower, but never a leader, in many of the key political and cultural campaigns of early twentieth-century Ireland including the turn of the century language revival, Sinn Fein from 1905 and the organisations of the revolutionary period including Cumann na mBan. She opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and was especially involved in left-wing and republican organisations in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1931 she travelled to Russia as a delegate of the Irish Friends of Soviet Russia. She was involved in the International Women’s League for Peace and Freedom and later in the Irish Housewives Association (established in 1942), although as a single, childless woman she abhorred the manner in which female activism assumed a maternalistic focus from the 1940s.

Rosamond Jacob was not a prominent figure in Irish history; she was a fringe activist, a foot soldier. Jacob was born in 1888 to lapsed Quaker parents in Waterford. The family were fully engaged in, and with, the political and humanitarian campaigns and ideas of the late nineteenth, early twentieth-century and Jacob’s childhood and adolescence was filled with debate and discussion on the Irish national question, the issue of female suffrage and the rights of both humans and animals. Jacob was a follower, but never a leader, in many of the key political and cultural campaigns of early twentieth-century Ireland including the turn of the century language revival, Sinn Fein from 1905 and the organisations of the revolutionary period including Cumann na mBan. She opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and was especially involved in left-wing and republican organisations in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1931 she travelled to Russia as a delegate of the Irish Friends of Soviet Russia. She was involved in the International Women’s League for Peace and Freedom and later in the Irish Housewives Association (established in 1942), although as a single, childless woman she abhorred the manner in which female activism assumed a maternalistic focus from the 1940s.

She was, as all human beings are, an interesting mix of convictions, contradictions and paradoxes; most notably she was forced to reconcile her commitment to pacifism with her republican sympathies. This contradiction, of course, played itself out in her relationship with Frank Ryan and there is the wonderful image of him secretly passing her a leather case at a Gaelic League meeting ‘with something hard in it’; she was to keep it safe for him which she duly did, her growing desire and attraction for him, her sense of the romance of him and his gunman image trumping her principles on occasion

Jacob was a novelist, not a very successful one, in her own lifetime. For historians these novels, particularly Callaghan (1920) and The Troubled House (written in the 1920s), are a wonderful key into her perspective on contemporary political campaigns and debates. A passionate believer in female equality, Jacob also wanted love, affection, marriage and children. Sadly, she was not to realize her desires and aspirations on these levels, causing her to experience much loneliness as she approached old age.

Diary

Jacob is unusual as a peripheral activist in having left to posterity a rich archive, most notably a daily diary maintained from 1897 until her death in 1960. This diary recorded in detail many of the debates and campaigns of Irish politics and cultural life. Until recently this diary has been mined by historians as a source to provide colour and context for work on the revolutionary period and early independent Ireland; it has been particularly used in this way by historians working on Frank Ryan offering as it does a key to aspects of a more private Ryan or an alternative perspective on his politics. Jacob was never behind the barricades of political and feminist activism in terms of assuming a leadership role but her life-long interest and participation in so many of the radical issues of the period draws attention to a broader-angle definition of activism. Her diary entries can be seen as a form of engagement in the body politic; through the diary entries and through her novels she can be viewed in the role of reporter or unofficial journalist, offering a perspective on how the central issues which shaped Irish politics and society in the first half of the twentieth century were experienced and digested by those outside the leadership cadre. The history of twentieth-century Ireland is, indeed, as much the history of more-ordinary political activists like Jacob as it is of leaders such as Frank Ryan and de Valera.

Jacob’s relationship with Ryan

From the perspective of the life of Frank Ryan, the diary offers a key to a more complex man than might be discerned from purely political sources and, of course, it offers a vantage point other than that of his own self-representation. Ryan and Jacob were lovers but this was no ordinary relationship, particularly in the context of Ireland in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Jacob first of all was much older than Ryan. Having met when Ryan began teaching Irish language classes through the Gaelic League, the relationship became sexual in 1928 when she was 40 and he 26, continuing with oscillating periods of intensity and disengagement until the mid-1930s.

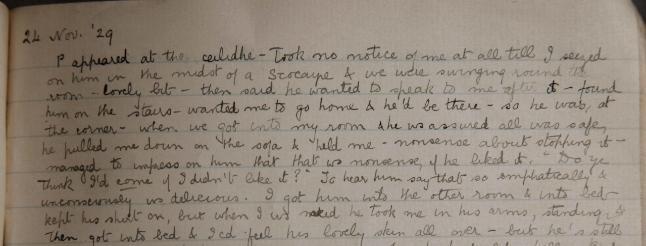

It is likely that for both of them this was their first physical relationship although Jacob does appear to have had some intimacy with the republican activist and journalist Robert Brennan in 1930. Indeed, she compared him with Ryan: ‘oh the difference between the touch of him & B – the intoxication of him in comparison’. Certainly both Jacob and Ryan were both inexperienced sexually: ‘I got him into the other room & into bed – kept his shirt on, but when I was naked he took me in his arms, standing & then got into bed & I cd feel his lovely skin all over – but he’s still inexperienced & I couldn’t get right, except for once when he hurt like hell’. Although neither of the two was committed to another the relationship has always been described as an ‘affair’.

For Jacob, Ryan was exciting and dangerous given his anti-treaty allegiance and his willingness to bring the gun into politics. He could be tender and affectionate but he was also increasingly infuriating as the years went on, refusing to acknowledge the relationship in public, not meeting her when arranged or arriving drunk late at night purely for sex. Physically intimate on occasions, he gave her little or nothing in terms of emotional intimacy or any expectation that the relationship might develop.

Yet Jacob herself never pressed him and in many respects, and interestingly, for such a self-avowed feminist, adopted a form of caring, domesticated role in his presence, feeding him, offering him shelter, money on occasion and running menial errands to support his political causes. Ryan, from the perspective of the diary entries, was disorganised and unreliable in terms of personal relationships and promises. He did not have any settled domestic life and at one particular point in early 1927 he found himself homeless; having lost his job in Mountjoy School due to his republican activities he was unable to pay his rent.

Morality, gender and power

It is noteworthy that Jacob never expressed any sense of wrongdoing in the context of the sexual nature of the relationship (unlike Ryan, who, although willing to stand against the Catholic Church in the context of his commitment to the use of physical force for political ends, believed he was committing a sin). Of course, the demand by him for secrecy, even to the point of ignoring her at social gatherings may reflect his sense of what he wanted from the relationship and his recognition of the age difference; Jacob, it must be said, allowed him to pursue a physical relationship with no ties. For Jacob, a single woman active at the fringes of illegal republican activities in the 1920s, to have a sexual relationship with Ryan was highly problematic and a potential source of shame and scandal in a way it would never have been for him. Despite being a lapsed Quaker the affair was scandalous given the dominant Catholicity of the Free State; Catholic sexual morality was one of the cornerstones of the new state’s identity. The ‘affair’, if considered from the perspective of Jacob, throws up some interesting points about the position of women in Irish society who did not fit neatly into the dominant domestic paradigm of wife and mother. It was very difficult to act as a sexually active single woman in the period. Full autonomy was not permitted to women such as Jacob by a society that refused to recognise the emotional and sexual needs of single women. Single women in this society were perceived as occupying a transitional space; the single woman who left her father’s home was in an ante-room, waiting to step into her own home and assume her marital role as wife and mother. Women such as Jacob who failed to marry but were not willing to embrace celibacy found themselves struggling to locate emotional and physical space in this environment. Forced to endure shared living space right into middle and old age due to the inability of single women to draw down mortgages and the lack of employment opportunities for her generation of women, Jacob found herself having to counter the hostility of women – such as Dorothy Macardle – to her life choices. Macardle ‘raged’ to her about the suitability of Ryan’s visits in the middle of the night and the two had to conduct their affair beneath her radar rather as errant adolescents rather than full-grown adults – indeed, adults approaching middle age in Jacob’s case.

Despite her feminist credentials Jacob had little power in the relationship; indeed the power balance was in inverse relationship to the age difference! Ryan had the power to pay her attention or not at public events and wielded it on occasion in ways that caused Jacob much hurt. While this may have had much to do with Jacob’s own personality and social ineptness it was also partly a mirror of contemporary social roles for men and women. In many respects the relationship was the defining experience in Jacob’s life. In February 1926 she wrote how – delightful as he was to listen to and look at in Gaelic League classes – she feared he would ‘spoil me for all other teachers’. More poignantly, it might be argued that the relationship ensured Jacob forged no other meaningful emotional or sexual ties in her lifetime. When Ryan went off to fight in the Spanish Civil War in December 1936 he failed to even contact her to say goodbye!

Dr Leeann Lane is head of the Irish Studies department at the Mater Dei Institute, a college of Dublin City University. She is author of Rosamond Jacob: third person singular (2010)